“About eight years ago, I decided I wanted to work with a Shakespeare [play] to do a new play,” said playwright James Ijames at the start of an April 9 post-show talkback of his new Broadway comedy “Fat Ham.” “Around the same time, I had made this decision that I wasn’t gonna write plays with sad endings; I only wanted to write plays with happy endings. This one was the first one where I felt like I was able to really achieve that. I wanted to take something that was known as tragic and make it into otherwise.”

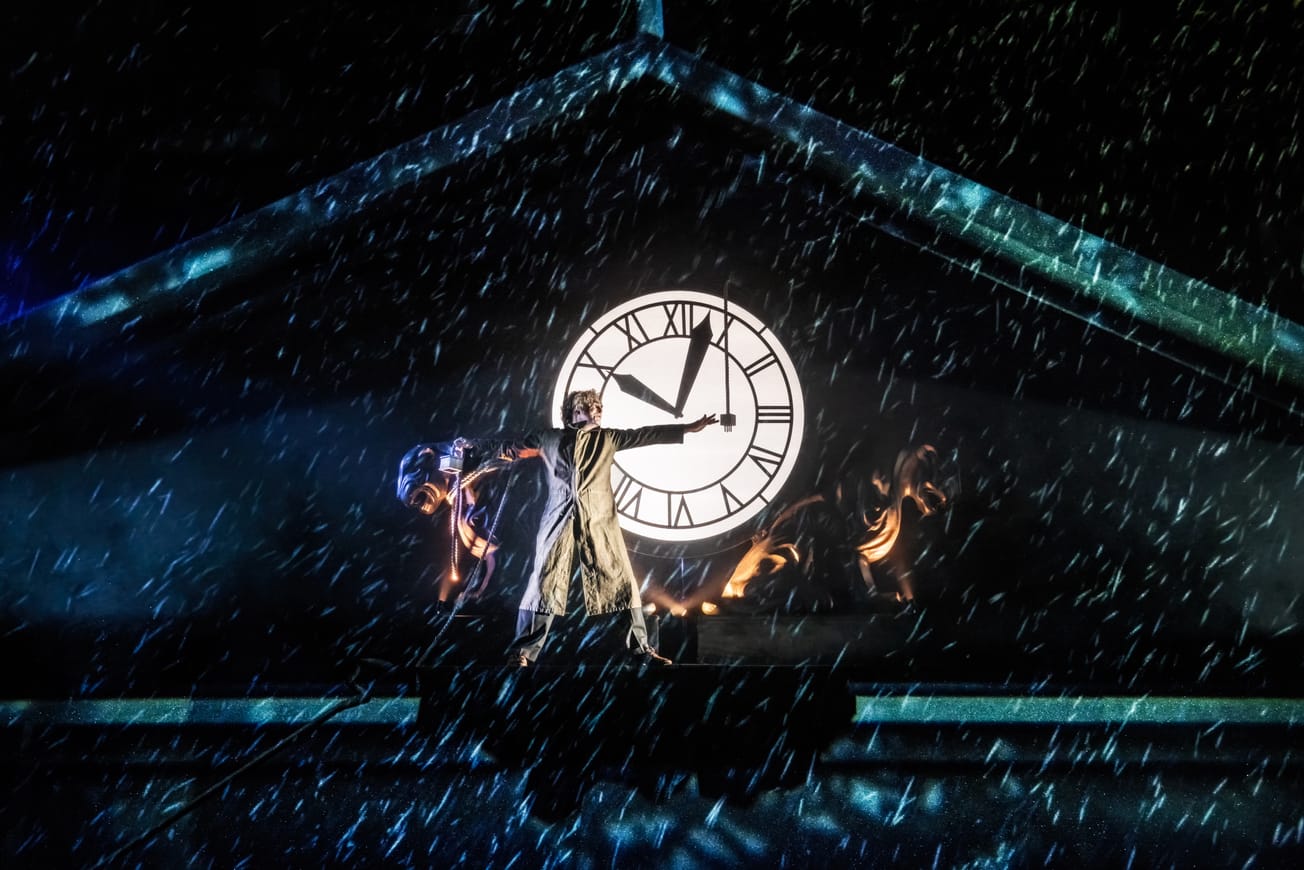

The Pulitzer Prize-winning play by Ijames (pronounced “Imes”) will officially open on April 12 at the American Airlines Theatre. Inspired by Shakepeare’s “Hamlet,” the comedy centers on Juicy (a young, queer, Black online-college student) and is set at a backyard barbecue celebrating the marriage of his mother, Tedra, to his uncle Rev, after Juicy’s father is shanked to death in prison. But the materialization of Juicy’s father’s ghost from the outdoor meat smoker complicates things even further for an already ostracized Juicy.

During Sunday’s post-show discussion, Tony Award-winning performer and “Fat Ham” co-producer Cynthia Erivo questioned the playwright about the combination of two ideas (Shakespeare and a barbecue) that on the surface appear totally unrelated. “How do those two things meet each other to create something?” she asked. “They don’t,” Ijames said with a laugh.

“I like tension,” he continued. “I think art is at tension points, and so you put these two things that you don’t think should go together: Black folks in the South eating at a barbecue and Shakespeare. You don’t expect those two things to work. Like — I’m gonna use a food analogy — when you’re craving something that’s sweet and salty … fries and ice cream. That shouldn’t make any sense, but like, have you done it? And that tension between the things that we think should be and what could be is magic for the theater.”

That tension is what Ijames specifically experiments with in every aspect of “Fat Ham” — particularly as it pertains to testing the interactions between onstage players and the audience. It’s one of the reasons he breaks the fourth wall early on in his script.

“The audience means everything to me — the crowd,” Ijames shared. “I don’t think about audience much. I think about crowd.”

In thinking about that for “Fat Ham,” the scribe considered multiple pathways of energy and its effects.

He pondered horizontal relationships (the interactions between one audience member and another, as well as the interplay between actors onstage) as well as vertical relationships — “what is happening onstage with you [the audience], specifically, and how that starts to mess with the horizontal relationships.”

That method of thinking affected how Ijames wrote the comedic dialogue, especially. “If [I] think about, ‘I know that this joke will probably land with a certain segment of the audience and another segment will have this joke,’ there starts to be this conversation that happens in the audience about what we [collectively] think is funny and what we think is moving.”

That collective, that unknowable chemistry, is what thrills Ijames. He wants to create conditions for clarity and permission.

“I think theater is a great space because you have to be in the same space to do it, and it forces people to imagine together,” he said. “Everybody in his room has to suspend their disbelief for however long the play is, to say, ‘Yes. I believe that that’s a ghost onstage.’ That offers people — and myself — the ability to imagine a different way for ourselves, or a different life.”