Earlier this summer, the Broadway League learned that the funds for the New York City Musical and Theatrical Production Tax Credit had been unexpectedly depleted. The program, colloquially known as the “downstate tax credit,” had been renewed in May as part of the New York State budget, passed under the leadership of Governor Kathy Hochul. The League had lobbied for this renewal of the credit, a program that began in 2021 under Governor Andrew Cuomo.

Passed in April 2021 (for fiscal year 2022), the state allocated $100 million to reimburse qualified production costs — 25 percent up to $3 million — as a tax credit to productions that applied and were subsequently approved. That $100 million was set for a one-year program, expiring on Dec. 31, 2022. But in April of 2022, Governor Hochul extended the credit to June 30, 2023, and raised the total available funds to $200 million. In May 2023, one month before the program was set to expire, it was renewed for two years — to June 30, 2025 — and the aggregate funds increased to $300 million. Finally, just a few months ago, Hochul extended the credit until June 30, 2027, and raised the aggregate amount to $400 million.

Essentially, the state government had begun by adding $100 million each year to the pool of funds from which producers would be reimbursed (as long as they were approved). But with the most recent renewals, the governor allocated an additional $100 million for two years.

Not only did the industry receive less money per year from the latest renewal, but the League and individual producers did not know how much money remained in the fund from previous years. Empire State Development, which administers the credit, only tracks the funds internally. “The data is only available to us if we send in a FOIA or a Freedom of Information Act request — which we’ve done — and it usually takes a few months to get the data,” said Jeff Daniel, head of the League’s government affairs committee and president of the Shubert Organization. “The last one we did was a December [2024] request, and it’s not as fulsome a data packet as you would like. It makes it very difficult to figure out what’s remained.” And the League does not have their own system in which the general partners across Broadway disclose what they have applied for, what has been approved and what has been reimbursed. As Daniel said, “It’s not that easy to do.”

What’s more, the $100 million per year may be less than what’s actually needed. “It was an estimate based on historically the number of plays and musicals [that open each year],” explained Daniel. “We used that data and the capitalization for those shows, and we [referenced] pre-COVID budgets.” But, according to producers, costs have increased dramatically.

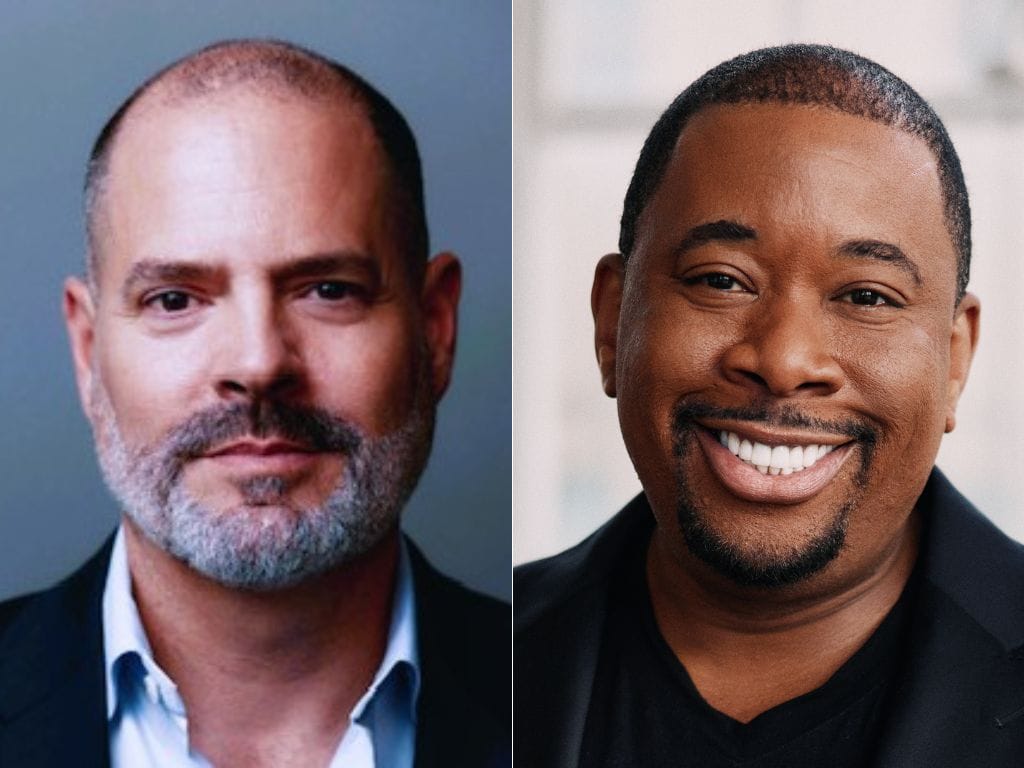

“The physical costs of goods has not reset to pre-pandemic numbers,” said four-time Tony Award-nominated producer Brian Anthony Moreland, who has served as lead producer on shows like 2022’s “Piano Lesson,” 2024’s “The Wiz” revival and 2025’s “Othello.” And Moreland said he expects that these increased costs will not rebound. This is the new normal. Moreland recalled capitalizing “The Piano Lesson,” which starred Samuel L. Jackson and John David Washington, for $7 million. “That was a lot for a play at that time,” Moreland said. “I wish it could be that number now.”

With the increase of costs, less money injected into the fund than past renewals and the difficulty of tracking the funds, the money available for reimbursement has now run out. There are productions in the 2025-2026 season that had anticipated being able to apply for the credit that now cannot. The League and many industry leaders are now lobbying the state to renew the program in the upcoming budget (rather than in 2027) — but with some changes.

Looking forward

The “respectful request,” as Daniel put it, is “a three-year period at $100 million per year. And I would say respectfully, an additional amount of money to look back and retroactively fund the shows that won’t get the credit [this season].” This would take Broadway to 2029 before another renewal would need to be considered.

Through the League, Daniel is also proposing some adjustments based on the success of a show. As the program is currently administered, producers that reach a certain level of recoupment pay back 50 percent of the credit over time — meaning that the most they would be reimbursed is $1.5 million. Looking forward, Daniel suggests changes both to the amount that recouped productions can receive and how they receive it.

“If a show is successful, then they wouldn’t get the full credit,” Daniel said. “They should be rewarded for taking the risk, but not to the full tune of $3 million.” The reimbursement would be a percentage of the potential $3 million, relative to the amount of success, and still would not exceed $1.5 million. “That will preserve more money for other shows.”

Daniel also wants to streamline the repayment process. “Instead of the credit being issued and the production taking the [full] credit and paying [a portion] back to the New York State Arts Fund [if they recoup], we just say truncate the eventual credit amount, or decrease it, for a successful show.”

“What we all on Broadway agreed to originally, and still believe, is that when a show is successful, those producers are more than happy to acknowledge that,” Daniel added.

As one of those producers, Moreland agreed. “There’s room to have conversations and guidelines in place that if … they reach these particular numbers, there’s an automatic reduction [of the reimbursement] or you are automatically no longer qualified or something.”

While Broadway is considering changes, Moreland thinks there’s room for another adjustment. “I also think they should think about having a different scale for musicals versus plays, because, although we are both shows, our cost structures are completely different,” he said. “$3 million to a play is amazing. It’s kind of a drop in the bucket on a musical that’s like $30 million.”

More than anything, “I really hope that people can see the need for it,” Moreland said of the downstate tax credit overall.

The credit was initially conceived to help reopen Broadway after the COVID-19 shutdown by offering an incentive to producers (and, in turn, their investors). And given the numbers Broadway reported in the 2024-2025 season, some may believe Broadway doesn’t need these funds. But there are economic reasons Broadway is still in need of the program and cultural reasons to rethink the paradigm of how the state funds the arts.

Economic value

In 2019, before the pandemic, Broadway generated $15 billion of economic impact for New York City, and today, according to Daniel, “our revenue has reached that and our audience has hit that now, and we’re not even at full capacity.” He continued, “We really fight well above our weight on Broadway because of our ability and [as one of] the reasons why tourists come to New York City. Then they stay in hotels, eat dinner, go shopping and fly in, park, all those things — not to mention our regional visitors and not even speaking to the cultural value.”

The League argues that the tax credit allows Broadway to remain robust and continue to deliver that $15 billion impact. “And, offensively, how do we move from $15 to $20 billion?” Daniel asked, noting that Broadway wants to help increase the city’s revenue. But that requires investment — specifically investment from the state. “Those [approximately] 40 different companies that open a show on Broadway every year, each one of those is individually capitalized,” Daniel noted. “It was a high-risk environment prior to COVID. Post-COVID, with our expense structure being at least 30 percent higher in the same revenue numbers, it is worse.”

“We have to compete and attract investors for each of the shows, and the tax credit is really crucial in doing that,” Daniel continued. “We’ve kind of crawled up a little bit and found ourselves back, at least, on the top line number [when it comes to Broadway’s season gross.] I think that top line number really hides the fact that the net numbers don’t work right now. So the credit is extremely helpful to investors in that regard.”

Over the 53 weeks of the 2024-2025 season, Broadway grossed $1,892,650,959. This is the highest-grossing season in recorded history. But that is the gross income.

“My grandfather told me something, trying to teach me a lesson when I was younger. He said, ‘It’s not what you make, it’s what you spend,’” Daniel said. “Broadway’s predicament right now is: We’ve certainly met our obligation to reopen and drive those international tourists and the visitors here — that means so much to the city and the state. But no one says, ‘Wait a second, what did you spend? How healthy are you?’”

“The tax incentive has become a crucial part to how to finance these really valuable little economic juggernauts that are shows on Broadway,” Daniel said.

Moreland knows this firsthand. Since reopening and the introduction of the tax credit, he has been able to 1) weather the early storms of the Omicron variant and its earlier-than-expected closing of his “Thoughts of a Colored Man,” 2) navigate performance cancellations as Broadway navigated cast illnesses, like with “The Piano Lesson,” 3) attract new investors and co-producers, and 4) plan better paths to recoupment for his productions.

“Having that tax credit was all about investor’s confidence in Broadway,” Moreland said. “That tax credit, offsetting 25% of that [cost], is a game-changer in the sense that [investors can recognize], ‘Okay, you can reach capitalization, and I also see that recoupment can happen faster because of this.”

And the speed of recoupment weighs heavily, in particular, on limited engagements.

“For example, if your recoupment chart says you can recoup in 17 weeks at 100 percent capacity, but you’re only running for 15 weeks, well, I might take that gamble depending upon what the other players are in the cast, on the team or what the subject matter might do in the market,” Moreland posited. “But if we are at 100 percent capacity and factor in the tax credit, well then we actually recoup in 11 weeks. There’s a possibility of four weeks of profit. So now I’m more likely to invest because I now have a pathway for recoupment.”

With the assistance of the tax credit, “The Piano Lesson” and “Othello” each recouped. Both were star vehicles of established titles — the aforementioned Jackson leading an August Wilson drama with Denzel Washington and Jack Gyllenhaal in a Shakespeare classic, respectively. But as Moreland noted, “Broadway is always a gamble.”

With “Othello” specifically, given that it was produced during the more stable 2024-2025 Broadway season, many might think Moreland wouldn’t need a tax credit reimbursement for the revival to be viable. “When you looked at our initial recruitment chart, the margins were slim,” he shared. “I had multiple people walk away from the production simply because they thought the margins were too small. There was no windfall on paper. We just happened to get lucky.”

But that experience, for investors, built confidence in the business. Moreland said that it also encouraged many to invest in other projects. It keeps the cycle of funding theater alive.

Cultural value

As part of the program, Broadway has also made good on pledges to provide free and discounted tickets to low-income New Yorkers. Additionally, to be eligible for the credit, a production must hire a fellow to provide job training to ensure a diverse population of future Broadway workers.

The tax credit is also a tangible demonstration of valuing theater, specifically Broadway and Off-Broadway. And while Broadway, in particular, has rendered New York City the unofficial international capital of theater, that status as the center of the art form is not a given.

While theater is burgeoning worldwide, London, in particular, has become a stronger competitor to Broadway when it comes to developing and launching new shows because of the lower cost and their own government tax credit. “There was a tax credit that was passed” for West End productions, said Daniel. “It’s lucrative, it’s regular and recurring — unlike ours — and then they made it permanent. It’s funded quickly. It’s easy to administer, and it’s extremely valuable.”

London has been a less expensive place to produce theater for years, “but with the credit over there, it really makes it attractive for risk-taking people to say, ‘I can survive a rough go of it or failure in the U.K. I don’t know if I can survive that risk here,” Daniel explained. “With the support of the governor, the argument is, ‘Take advantage of the credit here. You can go to the West End later. It needs to originate in New York. It needs to originate on Broadway.”

“That’s what we’re after to protect,” Daniel urged.

Broadway is already experiencing some effects from the lack of tax credit funds. Moreland said he and his producing peers are having “larger and longer conversations” with investors. “Investors are scared, but they don’t have all the actual details,” Moreland said. “So you need to give them data and give them different scenarios to help them understand what’s actually happening and the pros and cons of it. It’s a longer conversation before they invest. It’s also a deeper conversation with co-producers who now, more than ever, need more information to understand what’s happening on the inside.”

Daniel is concerned that it may be difficult to immediately discern the full effect. “Does it mean we flipped from $15 billion of our economic impact down to 12? Does it mean we see [fewer] original plays or new works on Broadway? Does it mean the big musicals just go to London and open and New York’s not the capital of new works anymore?” he wondered. “All those things are quite possible and they’ll be subtle. And what I’m really worried about is because they’ll happen slowly, we’ll look up in a couple of years and be in a very different place than we want to be.”

But the League is dedicated to ensuring Broadway doesn’t have to wonder. They have been lobbying Albany and demonstrating the necessity of both renewing the credit and making proposed changes. As Daniel said, “We’re going to do what we’ve done every year, which is advocate for Broadway, advocate for our workers, advocate for audiences.”