Theatrical translation is much more than converting words in the original language to words with equivalent meaning in a new one. Though a translation is nothing without meaning and clarity, those attributes are not enough. Theatrical translators must consider the style and tone of the show, the way in which language is used (differentiating direct and literal from poetic and beatific), linguistic history (matching words to the era in which the piece is set), cultural understanding (choosing references that ring true for a new audience), rhythm, phrasing and character.

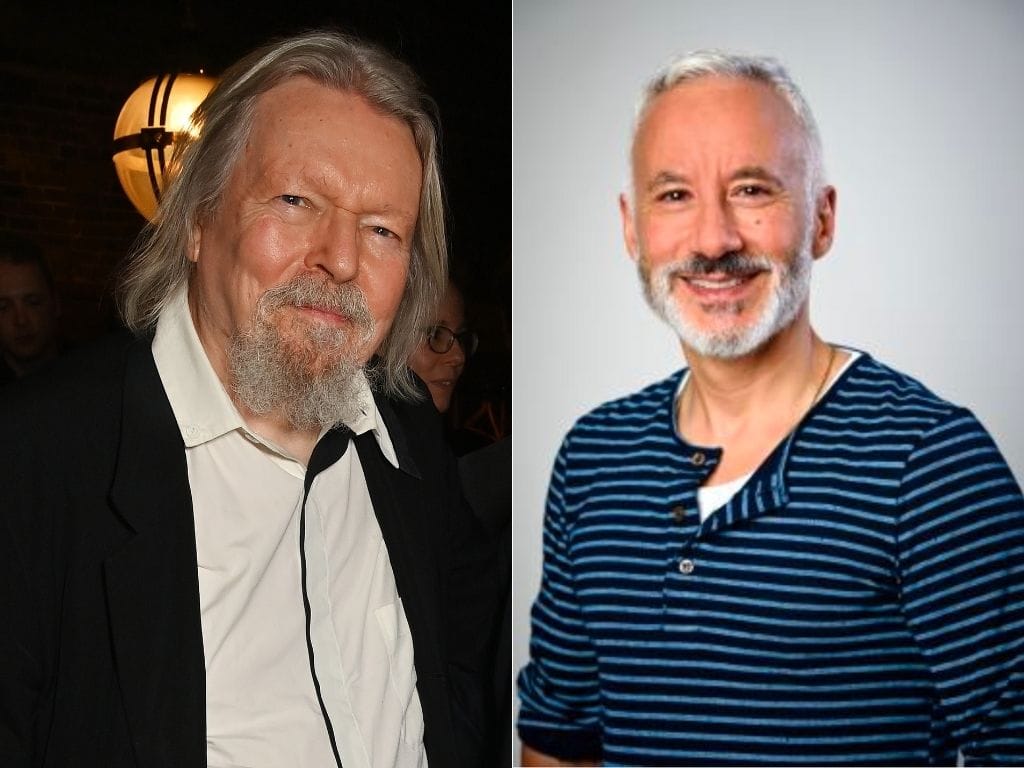

“It’s juggling with 10 balls at the same time,” said Daniël Cohen, a Dutch playwright, lyricist director and translator who has translated more than a dozen musicals from English to Dutch. At the end of the day, these myriad factors that translators consider combine to achieve a simple — if not easy — goal. “The aim is to try and deliver as accurate a translation as possible,” declared Christopher Hampton, a British playwright and translator who has translated dozens of plays into English. “Your duty really, as a translator, is to get out of the way and present as close as you can to what the author intended.”

On Broadway, it’s been historically rare for a musical to have originated in a language other than English. One of the most famous is the French “Les Misérables,” with lyrics by translator Herbert Kretzmer; the most recent is the Korean “Maybe Happy Ending,” translated by its original writing team, Will Aronson and Hue Park. More common is the export of American musicals to countries around the world, which require translation from English to other languages.

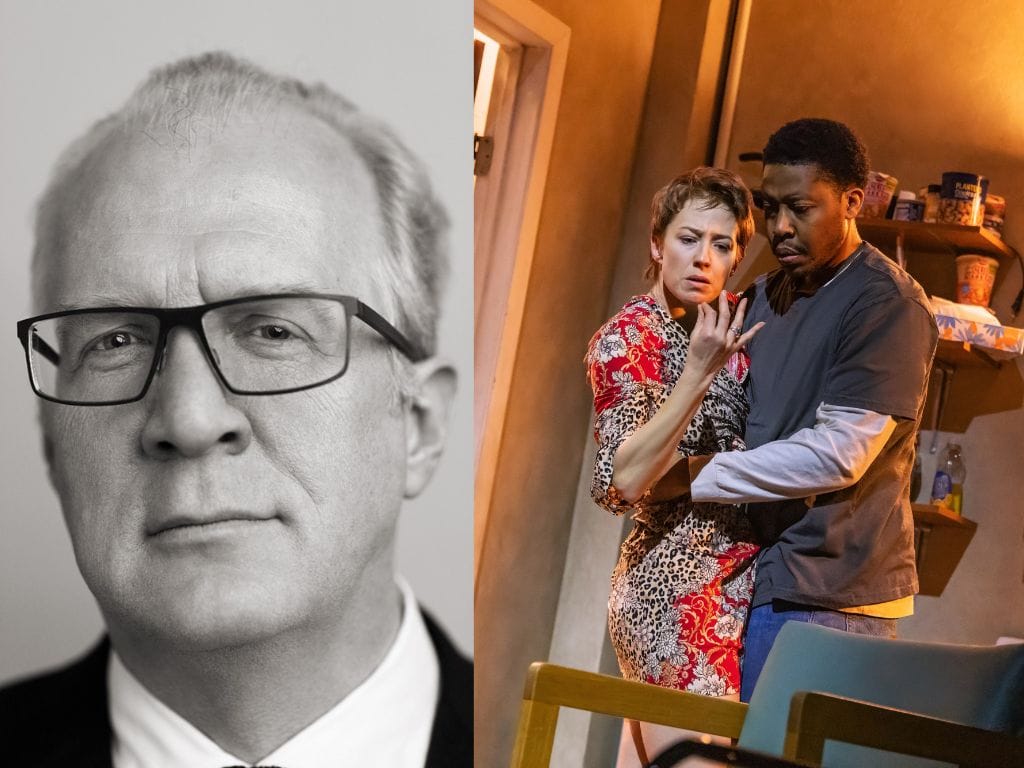

When it comes to straight plays on Broadway, there is a long tradition of English translations. Many of the so-called classics originated outside of English: Sophocles’ Greek, Chekhov’s Russian, Ibsen’s Norwegian, Molière’s French. Modern translations have been fewer and farther between. But the fall of this 2025-2026 Broadway season has welcomed three: Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot,” a translation from French to English by Beckett; Sophocles’ Oedipus, a new adapted English translation by Robert Icke; and Yasmina Reza’s “Art,” a revival of the Tony Award-winning play with translation from French to English by Hampton.

There is a distinct art to translation, a necessary discipline for cultural exchange. But, according to Hampton, the practice of hiring a specifically theatrical translator — rather than someone who can simply reword — is fairly new.

A tale of two translators

The distinction between academic and performative translation gained prominence in the 1960s, both according to this scholar and Hampton’s own experience.

Hampton began working for London’s Royal Court as soon as he completed university, and the Royal Court wanted to shake things up. “They had developed a theory that the classics ought to be translated by playwrights, not by academic translators because, prior to that, whenever there was an Ibsen or a Chekhov production, they would use the Oxford edition translated by some eminent linguist academic,” Hampton explained. But the Royal Court wanted to emphasize “speakable dialogue,” as Hampton put it. He was assigned Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya,” his first ever attempt.

But Hampton doesn’t speak Russian. The Royal Court paired him with a Russian woman who made a literal translation, then Hampton created the play version from that. Soon, he was called to do Ibsen (he doesn’t speak Norwegian). “I found that I really enjoyed the process of translation,” Hampton said of his early exposure to the job. “As opposed to writing your own own plays, it was like going to the gym or something. It was a linguistic exercise.”

Eventually, Hampton transitioned to translate French — a language in which he is actually fluent. Years later, that led him to Reza and “Art.”

Cohen took a different path to translation — one forged from necessity. As a theater director in Amsterdam, Cohen wanted to stage Stephen Sondheim’s “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.” “In my youthful arrogance, I thought, ‘Well, I’ve never done this before, but I’m sure I can do it,’” he recalled. Directing his own translated text confirmed firsthand the truth in the Royal Court’s 1960s theory. As Cohen said, “It taught me that all the things that I invented writing at my desk weren’t necessarily the best choices for the actors.”

How Hampton translates

Hampton describes translating as “a huge number of small decisions.” With a comedy, like “Art,” those choices are not only about how actors can perform the play, but how the text allows them to elicit laughter from the audience. “The way to do that is often the phrasing,” Hampton said. “That often has to do with word order.” Even in a straight play, there is musicality to consider.