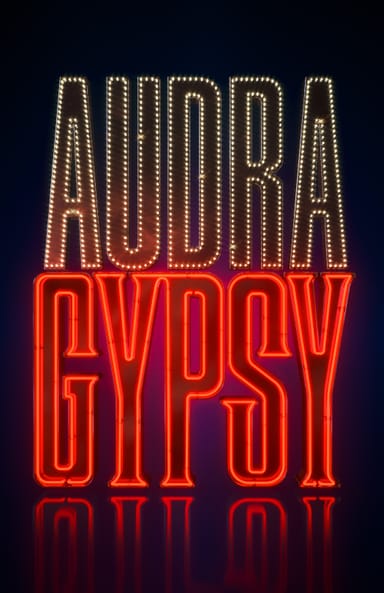

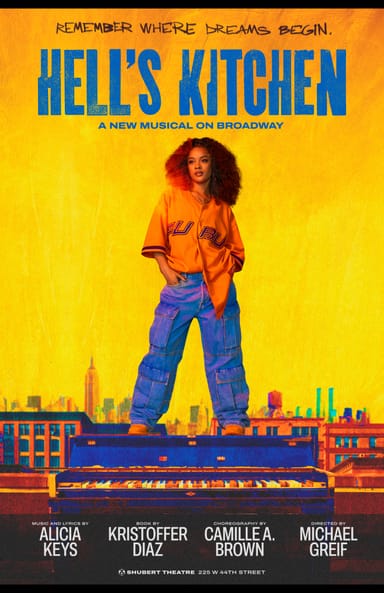

“I tell all the dancers that I’m working with, ‘You have your script and then you have your dance script,’” said choreographer Camille A. Brown, and she doesn’t just mean the list of steps. Brown, who recently earned her fifth Tony Award nomination, for the 2024 revival of “Gypsy,” is talking about the dramaturgy in her movement.

Brown is the first choreographer to completely reinvent the dance for a Broadway production of “Gypsy.” Every previous revival has used the original Jerome Robbins choreography. But that vocabulary is intrinsically part of Brown’s. “I know ‘Gypsy’ like the back of my hand,” she said. “It’s one of the shows I grew up on, that my mom introduced me to.”

So she has known the story of stage mother Rose, who created routines for her daughters, June and Louise, hoping to make them vaudeville stars — only for June to abandon her and Louise to become the burlesque superstar Gypsy Rose Lee. Brown’s vision closely tracks these three women and “their use of power,” as she said, through movement. Here, Brown analyzes the choreography in three of the show’s buzzed-about numbers.

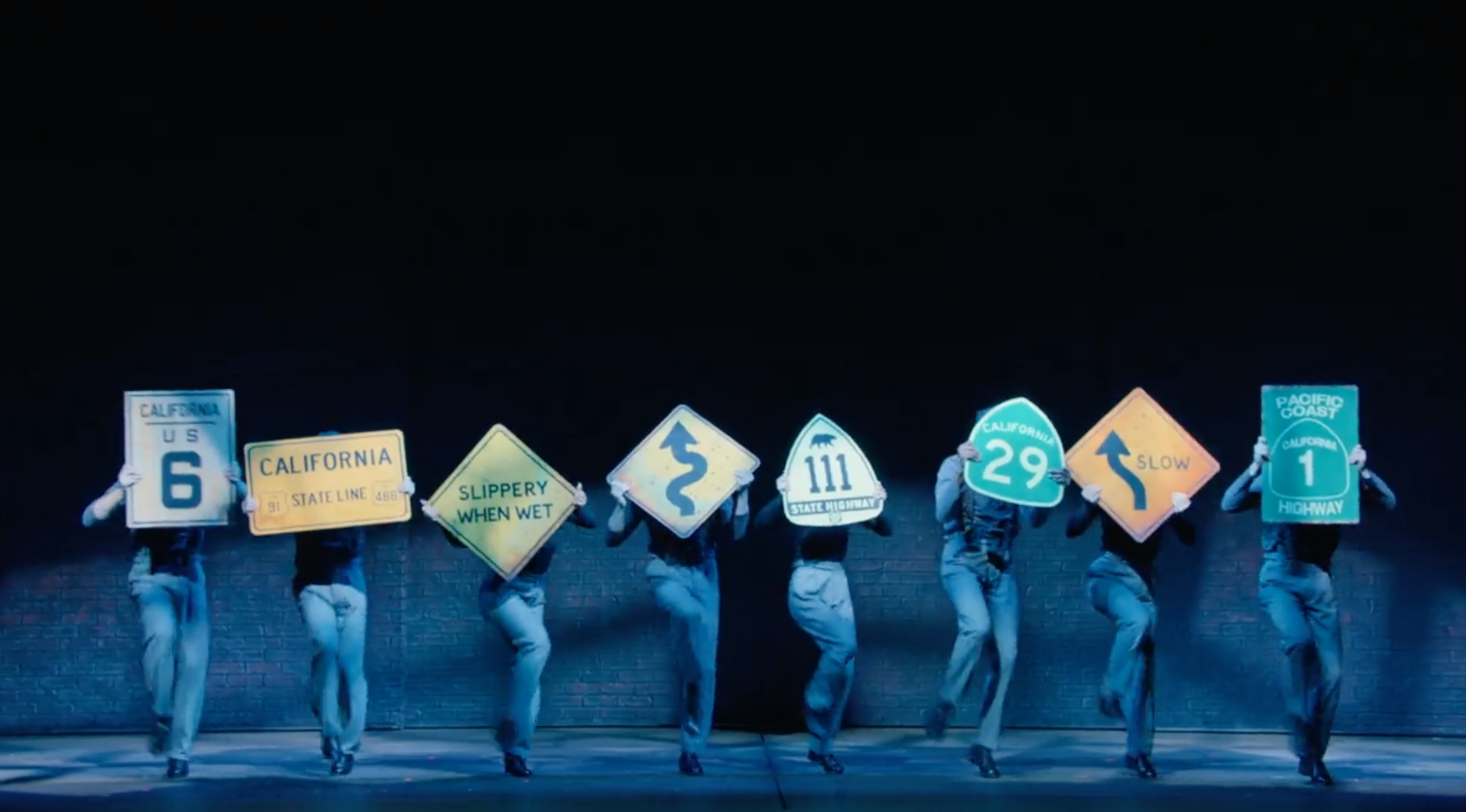

“Seattle to Los Angeles (Some People Reprise)”

“This one was the hardest for me to figure out,” Brown said. It may not feature epic lifts or four barrel turns (more below on that), but this sequence has a lot of narrative to communicate. Madame Rose takes her daughters on the road and finds the chorus boys for their act along the way. Brown’s dancers needed to hit clear beats and locations within George C. Wolfe’s direction. But Wolfe told Brown he didn’t want to see the young dancers’ faces; he wanted them to hold large road signs to illustrate the physical journey. “As performers, you use your face, but now you don’t have that. That means everything you would do [with facials] has to be translated from the waist down,” Brown said. “I wanted it to feel like it was whimsical and fun, and I had the image of those — is it Campbell Soup? — with the cans and then the legs showing. What if their legs were characters with the signs as the personality?”

Then, Brown had to conjure the movement of the road trip — the literal traffic pattern. “I wanted it to be just real smooth,” the choreographer described. “I’m orchestrating your eye. If this was a movie version, I wanted it to look like the signs were just rotating [zooming in and out]. It took a lot of time and repetition for me to see: You go for eight [counts], then you go for eight, you come in on four, you go downstage, you go back while that’s going forward.”

The whimsy Brown wanted for this number was inspired by the music. “That’s what it sounded like to me,” Brown said. “It just was, ‘I’m looking forward to this and the excitement of the unknown.’ There’s whimsy in that — and the joy of finding these kids. It’s kind of brutal what she’s doing [plucking these boys out to join them on the road], but I think it’s a fun ride — for her girls, for the kids that come on board. It’s an experience.”

“All I Need Is the Girl”

In this song, Tulsa, one of the boys in Dainty June’s act, imagines his own routine — if he were given the freedom to perform the way he wanted. He has all the ingredients, but needs a girl to be his partner. “We wanted the essence of Gene Kelly,” Brown said. “Through Kevin [Csolak]’s body and how he lives in my choreography, you get to see the essence of someone who has the potential to be really amazing if they were to get out of Rose’s claws. This was an opportunity to show that he was being held back in her show. We were talking about this a lot: What does choreography by Rose look like? It was her idea of what she thought Broadway was. Everything that I choreographed [from her perspective] was very up and light. Stepping out of that: What does it look like to see the jazz and the use of the plié?”

“There’s also the groove that she missed and is in Tulsa’s body. It’s influenced by my use of rhythm,” Brown continued. “One of the social dances I used was the Shorty George, just to show the looseness, because that’s not what she did in her shows. Then there’s this barrel turn windmill that I have him doing. He did two. And then I said, ‘Now do three. Now do four.’ It’s four, the edge of where he could go. There’s a part of dance and entertainment that we want things to feel easy. And then there’s a part of dance where, as an audience member, it’s entertaining when we see the fight. That’s what I was going for in those turns. A lot of times people think that dance should never show the work, and that’s not always the case. You need a mix because you want to root for that person. If everything feels easy, then you feel less inclined to root for that person. But if there’s a rawness there, you go, ‘Yes!’”

As Tulsa talks through the number, Louise envisions herself as the girl Tulsa needs — or, really, wants. “To me, it’s like a dream sequence — that’s why, even though she gets up and moves, she finishes exactly where she started. In this dream, she became his partner, and we could see how she wants and desires to be in some sort of partnership with Tulsa through her movement and the mimicking. It’s like they’re having this conversation back to back.”

“The Strip”

“This was a moment to really see a woman go from completely being ignored by her mother to being the center of attention,” Brown said of the final strip sequence Louise performs as her new burlesque persona, Gypsy Rose Lee. “The more we show that this girl did have the talent all along, for me, it makes you think, ‘What was Momma Rose looking at — or not?’”

That final strip is a “Salute to the Garden of Eden,” as noted in the script. “I was interested in incorporating the chorus of dancers because ‘The [Strips]’ that I’ve known, the dancers sing and go away. But I would just look at pictures of the Garden of Eden and how everything was based on Eve sitting there and having all of this vegetation and earth around her. And I thought, ‘What if the dancers embody that?’”

Actor Joy Woods’ movement as Louise is incredibly specific — a sharp slice of the hand, a lift of the chin, a look away from her subjects. “There’s something very exciting when somebody is orchestrating things around them and not looking at them,” Brown said. “She’s a queen, so she only exerts energy when she feels like it.”

Brown’s vision for “The Strip” is all about power. “What does power over the audience look like? What does power over your body look like? Burlesque is all about telling people where to look, when to look, how to look,” Brown said. “And the ease. This is a moment where — in complete opposition of Tulsa and wanting to see the work — we don’t want to see the work. It’s effortless. [Her garment] just happens to fall off.”

“The process of putting the strip together was also in conversation with the piece that I was doing for my dance company called ‘I Am,’” Brown added. “I feel like this number is ‘Louise’s Turn.’ And anything she does in ‘Louise’s Turn’ has to be based on her dialogue that she says with her mother afterwards: ‘I am Gypsy Rose Lee.’”